Food in Greece is never just fuel—it’s culture, connection, celebration, and at its best, a form of meditation. The Greek relationship with eating embodies principles that yoga philosophy teaches: presence, gratitude, moderation, pleasure without excess, and the understanding that nourishment operates on multiple levels—physical, social, emotional, spiritual. Yoga and food retreats in Greece explore this intersection, treating meals not as separate from practice but as extensions of it, opportunities to cultivate the same mindfulness, breath awareness, and presence that we bring to the mat.

The Mediterranean diet—recognized by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage and studied extensively for its health-promoting properties—provides the perfect foundation for exploring mindful eating. This isn’t a diet in the restrictive modern sense but a way of life developed over millennia in the specific conditions of the Mediterranean basin. Olive oil in abundance, vegetables and legumes as primary foods, whole grains, fresh fish and seafood, modest amounts of cheese and yogurt, wine in moderation, minimal meat, and meals always shared and savored rather than rushed. These aren’t arbitrary rules but responses to what grows well in Mediterranean soil and climate, what nourishes bodies doing physical work in hot conditions, and what creates the conditions for longevity and wellbeing.

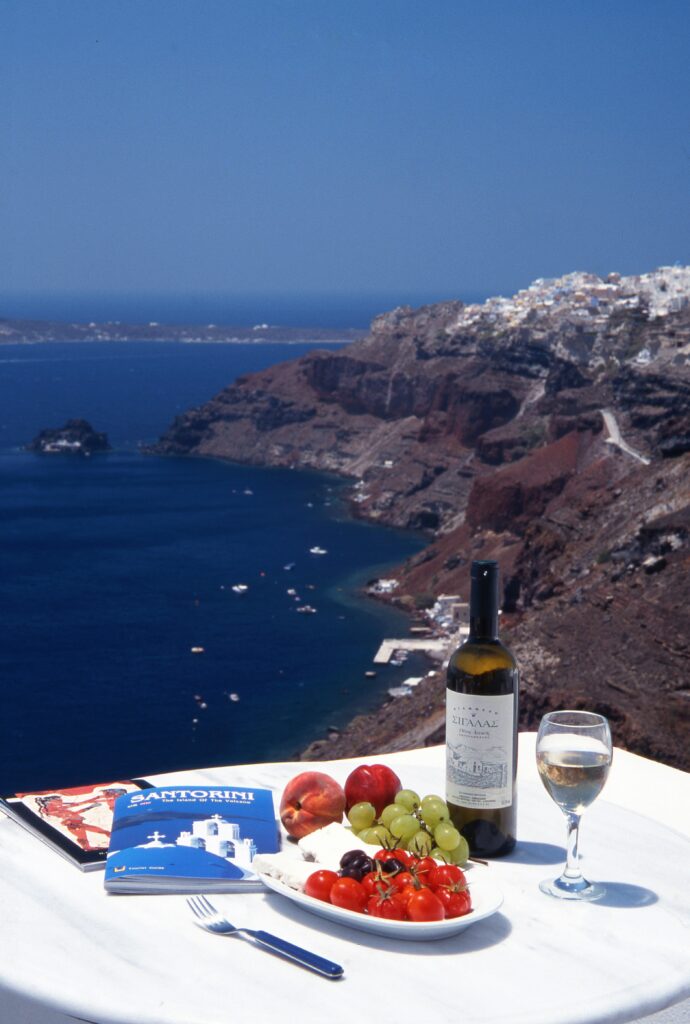

Yoga and food retreats in Greece invite you to slow down enough to actually taste what you’re eating, to understand where food comes from and how it reaches your plate, to cook with attention and care as a practice of creativity and service, and to experience eating as communion—with the earth that produced your meal, with the people who grew and prepared it, and with those gathered around the table sharing it. This isn’t about learning recipes to recreate at home (though you will), but about transforming your relationship with food itself, recovering pleasure and simplicity in an arena where modern life has created enormous complexity and anxiety.

The Mediterranean Diet: More Than a Food Plan

Understanding the Mediterranean diet requires moving beyond nutritional reductionism—the tendency to analyze food solely through macronutrients, vitamins, and calories—toward a more holistic view that includes how food is grown, prepared, and eaten. Research into Mediterranean populations with exceptional longevity and low rates of chronic disease points to the entire food system, not just what’s on the plate.

The nutritional components are straightforward: olive oil as primary fat source (providing monounsaturated fatty acids and polyphenols), abundant vegetables both cooked and raw (fiber, vitamins, minerals, antioxidants), legumes several times weekly (protein, fiber, complex carbohydrates), whole grains (sustained energy, B vitamins), fish and seafood regularly (omega-3 fatty acids), moderate amounts of cheese and yogurt from sheep and goat milk (protein, calcium, probiotics), small portions of meat (primarily for flavor rather than as main protein source), fresh fruit as typical dessert (natural sugars with fiber), red wine in modest amounts with meals (resveratrol and social pleasure), and herbs and spices generously (flavor, antioxidants, reduced need for salt).

But equally important are the practices surrounding food: eating seasonally and locally (maximizing nutrient density and freshness), cooking at home with simple methods that preserve nutrients, sharing meals with family and community (social connection, slower pace, conversation), eating sitting down without distraction (mindfulness, satiety cues), and treating meals as events worth lingering over rather than obligations to dispatch quickly. Greek meals traditionally last hours not because the food takes that long to eat but because eating is the framework for being together, talking, laughing, and simply enjoying each other’s company.

Yoga and food retreats in Greece teach this complete system—not just what to eat but how to source, prepare, serve, and consume food in ways that nourish every dimension of human wellbeing.

From Garden to Table: The Complete Food Journey

Many yoga retreats incorporate the entire food cycle into their programs, helping you understand and participate in the journey from seed to compost.

Growing and Harvesting: Morning might include garden work—weeding, watering, harvesting vegetables for lunch, collecting herbs. This isn’t performative farm cosplay but actual participation in food production. You learn which greens grow wild and are foraged rather than cultivated (Greeks are passionate foragers, gathering horta—wild greens—from hillsides and fields). You discover that tomatoes warm from the vine taste fundamentally different than refrigerated supermarket versions. You understand the labor involved in producing food and develop different relationship with waste when you’ve seen the work required to grow what you’re throwing away.

Some retreats time visits to coincide with harvests—olive harvest in late autumn/early winter, grape harvest in September, vegetable harvests throughout summer. Participating in these traditional seasonal activities connects you to rhythms that modern food systems have obscured. Picking olives by hand from ancient trees, pressing them at the local mill, and tasting the green, peppery oil days later creates visceral understanding of where olive oil comes from that no amount of reading can provide.

Market Visits: Weekly or twice-weekly markets remain central to Greek food culture. Retreat excursions to local markets teach you to select produce by season, quality, and ripeness rather than by aesthetics or year-round availability. You learn to haggle (expected and enjoyed in Greek markets), to communicate with vendors who speak minimal English, and to recognize varieties you’ve never encountered—the small, intensely flavored Greek tomatoes, the enormous white eggplants, the fresh almonds in spring, the dozens of olive varieties.

Market visits also reveal food economics. Organic local produce costs more than conventional but less than organic imports. Supporting small producers creates economic relationships that maintain agricultural landscapes and traditional knowledge. The woman selling her family’s olive oil, the farmer offering vegetables from his terraced plots, the cheese-maker whose goats graze nearby hills—these aren’t anonymous transactions but exchanges embedded in community and place.

Cooking as Practice: The heart of food retreats is time spent in the kitchen, learning not just recipes but approaches—how to cook by taste and intuition rather than precise measurement, how to improvise with what’s available, how to use simple techniques that maximize flavor while preserving nutrients, and how to cook for others as an act of care and creativity.

Greek cooking is remarkably forgiving and accessible. Many traditional dishes involve variations on a theme: vegetables stewed in tomato and olive oil (ladera), vegetables or seafood baked with herbs and lemon, various forms of pie made with phyllo dough or hand-stretched pastry. The techniques are straightforward; the magic comes from ingredient quality and patient, attentive preparation.

Cooking sessions at retreats are communal and social. Someone chops vegetables, another stirs sauce, a third shapes pies, someone else sets the table. You talk while working—about the recipe’s origins, variations family members make, memories associated with the dish. The process becomes meditation not through silence but through shared focus and creativity. And the meal that follows tastes better for having been made together, for carrying everyone’s effort and attention.

Signature Greek Foods and Their Preparation

Food retreats in Greece typically focus on teaching core dishes that represent the cuisine’s principles and that can be recreated at home with reasonable ingredient access.

Olive Oil: Understanding Greek cooking requires first understanding olive oil—not as generic cooking fat but as ingredient with enormous variation in flavor, quality, and appropriate use. Retreats often include olive oil tastings, teaching you to recognize good oil (fruity, slightly bitter, peppery finish), to distinguish varietals, and to appreciate that different oils suit different purposes. Fresh, high-quality extra virgin olive oil isn’t cooked but used raw—drizzled on finished dishes, mixed into sauces, the primary fat in salads. Lesser quality oil is used for cooking. The revelation for many participants is that properly used, olive oil doesn’t make food heavy or greasy but adds richness, carries flavors, and creates satisfaction that allows you to eat less while feeling more nourished.

Horiatiki (Greek Salad): The humble Greek salad becomes revelation when made properly—ripe tomatoes cut in chunks (never sliced), cucumber, green pepper, red onion, Kalamata olives, good feta cheese crumbled on top, dried oregano, and a generous pour of olive oil with a splash of vinegar. No lettuce. The key is ingredient quality and proportions—letting tomatoes dominate, using enough oil to dress rather than drown, allowing the dish to sit briefly so flavors marry. Properly made, this simple salad becomes a complete meal, satisfying and nourishing in ways that elaborate salads with dozens of ingredients rarely achieve.

Ladera (Vegetables in Olive Oil and Tomato): This category includes dishes like fasolakia (green beans), bamies (okra), and arakas (peas) all cooked slowly in tomato sauce with onions, herbs, and abundant olive oil. The cooking method—low heat, extended time, vegetables cooked until very soft—differs from modern preferences for crisp vegetables but creates something comforting and satisfying. These dishes are traditionally served lukewarm or room temperature, showing that good food doesn’t require constant reheating. Learning to make ladera teaches patience (you can’t rush the process), simplicity (few ingredients, minimal technique), and the magic of olive oil (added at the beginning for cooking and at the end for richness).

Dolmades (Stuffed Grape Leaves): The meditative work of rolling dozens of tiny stuffed packages—rice, herbs, sometimes ground meat, wrapped in grape leaves—represents cooking as practice beautifully. The repetitive motion becomes almost hypnotic. Hands learn the right amount of filling, the proper tightness of rolling. You understand why Greek women gather to make these together, talking while working, the social aspect as important as the food itself. When you later eat what you’ve made, cold with lemon juice, you taste not just rice and herbs but the care and time invested in preparation.

Spanakopita and Other Pites: Greek pies made with phyllo dough or handmade pastry and filled with spinach, cheese, leeks, or other vegetables are staples. Learning to work with phyllo—brushing each tissue-thin sheet with olive oil or melted butter, layering to create flaky texture—requires patience and gentle touch. Some retreats teach making pastry by hand, rolling it paper-thin (a skill older Greek women possess but younger generations often haven’t learned). The satisfaction of producing golden, crisp pies from your own hands creates confidence that extends beyond the kitchen.

Tzatziki and Other Dips: Greek meals always include mezze—small dishes shared before or alongside main courses. Tzatziki (yogurt with cucumber, garlic, and dill), melitzanosalata (eggplant dip), htipiti (feta and red pepper spread), and taramosalata (fish roe spread) are standards. Making these teaches the principle of creating big flavors from simple ingredients, the importance of resting time (most dips improve after sitting for hours or overnight), and the pleasure of meals composed entirely of small shared dishes rather than individual plates.

Fresh Fish: Greek cooking treats fish with respect and simplicity—grilled whole with lemon and oregano, baked with tomatoes and herbs, or occasionally in fish soup. The principle is never to obscure quality fish with heavy sauces or complex preparations. Learning to prepare fish Greek-style teaches confidence in simplicity and attention to proper timing (fish cooks quickly and becomes unpleasant when overdone). Many retreats include fishing village visits, buying fresh catch directly from boats, and preparing it the same day—experiencing the taste difference freshness makes.

Wine, Spirits, and Mindful Drinking

Greek food culture includes alcohol, but in specific contexts and ways. Wine accompanies meals—never drunk for its own sake but integrated with food, conversation, and company. The quantities are typically moderate (a glass or two over the course of a long meal), and the quality is improving dramatically as Greek wine-making modernizes while preserving indigenous grape varieties.

Food and yoga retreats address alcohol thoughtfully rather than ignoring it or treating it as incompatible with wellness. You might visit wineries, learning about terroir, varietals, and traditional production methods. Wine tastings teach you to drink slowly and attentively, noticing flavors, pairing with foods, appreciating quality over quantity. The approach is neither abstinence nor indulgence but mindfulness—being fully present with what you’re drinking, noticing how it affects you, choosing consciously rather than automatically.

Greek spirits—ouzo, raki, tsipouro—also appear, usually as digestifs or accompaniments to mezze. The ritual of ouzo with small plates of seafood, sipped slowly over hours, represents the Greek understanding that eating and drinking are frameworks for connection and presence rather than tasks to complete.

Eating as Meditation: Mindfulness Practices

Yoga and food retreats incorporate formal mindfulness practices around eating that deepen your relationship with food beyond cooking skills.

Silent Meals: Occasionally, usually early in the retreat, meals are eaten in complete silence. This feels awkward initially—we’re so habituated to eating while talking, working, watching screens. But silence creates space to actually taste food, to notice textures and temperatures, to observe hunger and satiety signals rather than eating mechanically until the plate is empty. You discover that food tastes more intense when attention isn’t divided, that you feel satisfied with less when you’re actually present with eating.

Gratitude Practices: Before meals, the group might pause to acknowledge the food’s journey—sun and soil that grew vegetables, work of farmers and cooks, privilege of abundance when many have little. This isn’t performative spirituality but genuine recognition of interdependence, of the countless conditions required for any meal to appear before you. Regular gratitude practice shifts eating from entitled consumption to humble receiving.

Slow Eating: Greek meals naturally encourage slow eating—multiple courses, conversation, wine sipped rather than gulped—but retreats make this explicit. You might practice taking small bites, chewing thoroughly, putting down utensils between bites, noticing when you’re comfortably satisfied rather than eating until uncomfortably full. The practices feel strange initially because they’re so contrary to modern rushed eating, but they reveal how much we typically eat on autopilot, disconnected from body signals and actual enjoyment.

Mindful Shopping and Cooking: Mindfulness extends beyond consumption to the entire food cycle. Shopping becomes practice in conscious choice—reading labels, selecting seasonal items, supporting small producers. Cooking becomes meditation—the sound of knife on cutting board, smell of onions sautéing, texture of dough under hands. Cleaning up becomes practice in completing cycles rather than rushing to the next thing. Every aspect of relating to food offers opportunity for presence and attention.

Nutrition Science Meets Tradition

While honoring traditional food wisdom, good food retreats in Greece also incorporate contemporary nutritional understanding. You learn why olive oil’s monounsaturated fats support heart health, how legumes provide complete protein when combined with grains, why tomatoes cooked with olive oil allow better absorption of lycopene, how fermented foods like yogurt support gut health, and why eating seasonally and locally maximizes nutrient density.

This integration of ancient practice and modern knowledge creates confidence that traditional ways weren’t just superstition but encoded wisdom about optimal nutrition. You understand that your Greek grandmother’s insistence on olive oil, horta, legumes, and slow eating wasn’t arbitrary but reflected deep knowledge about what sustains human health and happiness.

Workshops might address specific topics—gut health and fermentation, anti-inflammatory foods, protein needs and plant-based eating, sugar and refined carbohydrates, supplementation vs. food-based nutrition. The approach is never dogmatic but informational, providing tools for making choices that work for your body and life rather than prescribing rigid rules.

Sustainability and Food Ethics

Food retreats in Greece increasingly address ethical and environmental dimensions of eating. You learn about overfishing in the Mediterranean, sustainable seafood choices, the environmental impacts of industrial meat production vs. small-scale local farming, plastic pollution in food packaging, food miles and carbon footprints, and how food choices affect soil health, biodiversity, and climate.

These conversations acknowledge tensions between personal health optimization and broader ethical concerns. The most sustainable diet might not be identical to the most personally optimal one. Perfect consistency is impossible in modern food systems. But awareness and intention matter—making better choices more often, supporting systems aligned with your values when possible, accepting imperfection while still striving for improvement.

Some retreats partner with local organic farms, sustainable fisheries, or food rescue operations, allowing participants to see and support alternatives to industrial food systems. These connections often continue after retreats end, with participants seeking similar relationships in their home communities.

Bringing It Home: Integration Challenges

The most common question at food retreats is “How do I maintain this when I return home?” The challenge is real—replicating the Greek food experience requires time, ingredient access, and social structures that modern life doesn’t always provide. You can’t necessarily shop at markets three times weekly, you probably don’t have family members who’ll cook with you for hours, you may not have easy access to high-quality olive oil or seasonal organic produce.

Good retreats address this honestly, helping you identify what aspects are most important and most feasible to maintain. Maybe it’s not the specific dishes but the principles—eating more vegetables, cooking at home more often, taking time to actually taste food, sharing meals without screens or multitasking. Maybe it’s one Greek dinner weekly where you cook properly and eat slowly rather than trying to transform all eating overnight. Maybe it’s sourcing one or two key ingredients—really good olive oil, good bread from a local bakery—that elevate simple meals.

The goal isn’t perfect replication but sustainable improvement. You return with expanded cooking skills, deeper understanding of what real food tastes like, embodied knowledge of how slow, mindful eating affects satiety and satisfaction, and confidence that delicious, nourishing meals don’t require elaborate preparation or exotic ingredients. These shift your relationship with food in ways that persist even when you can’t recreate the perfect Greek meal.

Who Thrives at Food-Focused Retreats

Yoga and food retreats appeal to those who love eating and cooking and want to deepen those pleasures rather than restrict them, who’re interested in food origins and preparation not just consumption, who enjoy hands-on learning and don’t mind getting messy in kitchens and gardens, and who appreciate that the social aspects of eating matter as much as nutrition.

These retreats work beautifully for people recovering from disordered eating or diet culture damage, as they emphasize pleasure, sufficiency, and intuitive eating rather than rules and restriction. They suit travelers who want to understand Greek culture through its most accessible and universal medium—food. And they attract anyone who senses that modern eating has become complicated and anxious and yearns for simpler, more joyful relationship with food.

They’re less ideal for those wanting intensive athletic yoga practice (food-focused retreats emphasize moderate practice since you’re eating well and spending time cooking), anyone with severe dietary restrictions that Greek cuisine can’t easily accommodate, people uncomfortable with alcohol in any context, or those preferring their yoga practice separate from other activities.

But for those called to them, yoga and food retreats in Greece offer something precious—the recovery of eating as celebration rather than problem, as source of connection rather than anxiety, as daily practice of gratitude and presence. You learn that nourishment isn’t just about nutrients but about beauty, care, community, and the profound pleasure of sharing good food with others in places where food culture still remembers what truly sustains human beings.

More About Yoga and Wellbeing in Greece

Yoga and Food Retreats in Greece: The Healing Power of the Mediterranean Diet

Food in Greece is never just fuel—it’s culture, connection, celebration, and at its best, a…

Yoga and Detox Retreats in Greece: Reset Under the Sun

The concept of purification through fasting and cleansing is hardly new to Greece. Ancient Greeks…

Yoga and Sailing Retreats in Greece: Freedom on the Aegean Sea

There’s something profoundly liberating about waking up in a different bay each morning, about having…

The Light of Greece: A Meditation on Simplicity

There’s something about the light in Greece that’s impossible to photograph, difficult to describe, but…

Eco Yoga Retreats in Greece: Between Olive Trees and Blue Horizons

There’s an inherent alignment between yoga philosophy and ecological consciousness—both invite us to recognize our…

Yoga Retreats Near Athens: Balance Beyond the City

Athens doesn’t immediately conjure images of wellness retreats. The Greek capital is known for its…